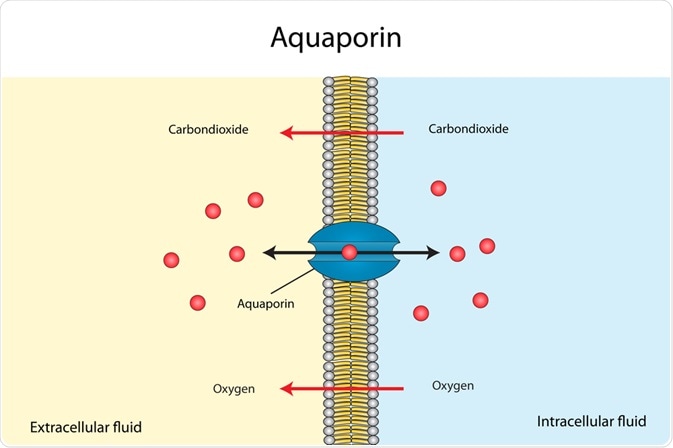

Aquaporins are a family of small membrane proteins widely expressed by plant and animal cells. They bear a similar basic structure in whichever organism they are found, consisting of six transmembrane helical segments and two additional short helical segments surrounding cytoplasmic and extracellular vestibules, with a narrow pore running through the center to allow the passage of small molecules.

Image Credit: W.Y. Sunshine/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: W.Y. Sunshine/Shutterstock.com

In most cases, water is transported through aquaporins, as implied by the name, as an active response to osmotic gradients. The narrow aperture of aquaporins makes transport slow, and thus cells utilizing them often express them in very high density on the cell surface. Steric and electronic interactions assist in the selective passage of water molecules, and sub-types of aquaporins have evolved to alternatively transport hydrophobic molecules such as glycerol.

Some evidence suggests that aquaporins may also be involved in the transport of gasses, ions, and other solutes, and may additionally be involved in cell-cell adhesion and extracellular protein interaction.

As described, some cells may require greater than average water or glycerol permeability, and thus express a high density of aquaporins or aquaglyceroporins. For example, where fluids such as saliva secrete across epithelial layers a high level of water permeability is required of the cell membrane.

The liver, kidneys, lungs, eyes, gastrointestinal organs, and many glands throughout the body frequently bear high levels of aquaporins, with other organs such as skeletal muscle and non-electrically excitable neurons also expressing some form of the membrane proteins.

However, in these cases, the proteins do not always appear to play roles in fluid transport and are usually reserved for high-throughput areas such as the proximal tubules of the kidneys.

The large surface to volume ratio of single-celled organisms ensures that osmotic equilibrium is rapid, and thus they have less need for aquaporins. They have been demonstrated to express them in some form, however, and they have been implicated in maintaining water permeability in freezing conditions. Plants possess a diverse range of aquaporins that have evolved to fill a variety of roles besides osmotic regulation, such as metabolism and reproduction.

Aquaporins in disease

Aquaglyceroporins are found in the epidermis, and mice lacking these proteins exhibit poor skin hydration and elasticity due to the resulting lesser concentration of glycerol in the tissue. Mice with impaired glycerol efflux in adipose tissues also exhibit progressive obesity, with the adipose tissue growing over time.

Some cancers have been observed to cause altered aquaporin expression levels in a varied manner, depending on where they are found and the causative mutations behind them. Greater expression of these proteins in cancer cells has also been associated with increased metastasis, though significant evidence of correlation is yet to be presented, and reports are conflicting.

For example, and intriguingly with a view to potential cancer therapeutics, mice lacking particular sub-types of aquaporin have been seen to demonstrate a heightened resistance to skin cancers.

Only a very few mutations to aquaporins are known to be involved in disease in humans, one being diabetes insipidus, a hereditary disease characterized by loss of function in AQP2, which transports water from the kidney beyond the surrounding epithelial layer. Defects in this protein result in the excessive production of dilute urine, as water cannot escape back into the body, as part of the normal process of the kidney.

Another mutation, this time in AQP0, which is found in the lens of the eyes, is associated with the development of congenital cataracts, though the reason is not yet completely clear. Beyond these, only occasional mutations and autoantibody conditions towards aquaporins have been reported, none associated with a major disease condition.

The potential of aquaporins as a therapeutic, therapeutic target, or diagnostic tool has been explored in a number of contexts, particularly cancers, where they are often overexpressed on the cell surface and thus make good complimentary receptors for fluorescent tags and drug delivery vehicles.

Control and manipulation of the population of aquaporins presenting on a cell could provide a future therapy, lessening the rate of metastasis of cancer cells and restoring tissue function. Patients suffering from Sjögren’s syndrome, characterized by dysfunction of the lacrimal and salivary glands, experience debilitating dry eyes and mouth, and corrective gene therapy of mutated aquaporins in mice was able to alleviate this condition.

Further Reading