Malaria is a parasitic disease of human beings. It is transmitted in 108 countries, in total affecting around 3 billion people. In 2010, it caused an estimated 216 million cases and 655,000 deaths.

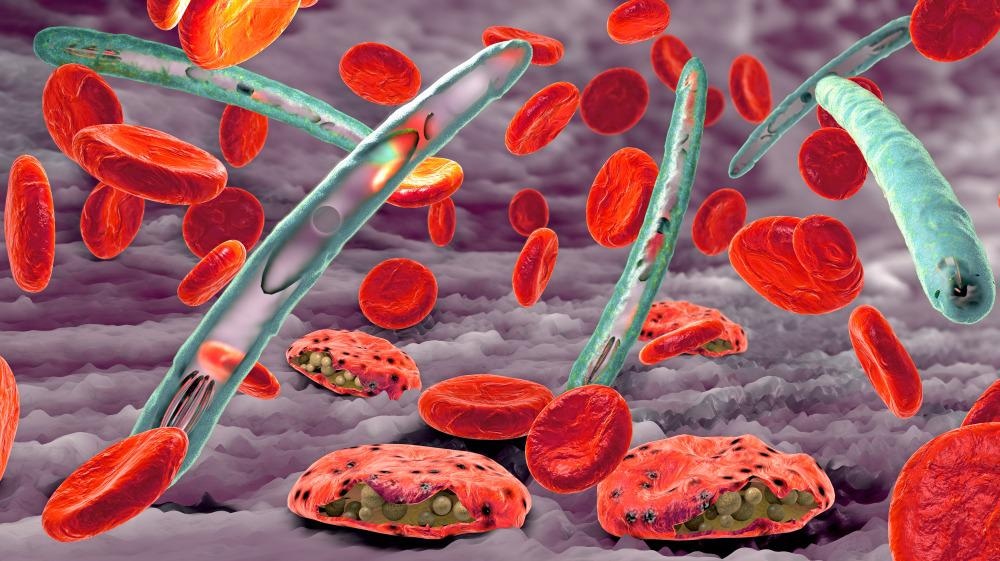

Malaria. Image Credit: Christoph Burgstedt/Shutterstock.com

Malaria is a protozoan disease transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease is attributed to five species of the unicellular protozoan parasite genus Plasmodium - the P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi. The latter (P. knowlesi) causes zoonotic malaria and is maintained in macaque monkeys in the southeast of Asia. All species share a lifecycle of two parts – infection of the vertebrate host and transmission from the infected vertebrate host to another by an insect vector.

Plasmodium species infecting humans share a similar life cycle. This life cycle consists of an initial development phase in the liver, followed by later proliferation in the blood of the host. These species also show similar susceptibility and resistance to some antimalarial drugs – these include quinine, artemisinin, chloroquine. Systemic control programs that use the appropriate chemotherapy, as well as the appropriate members of the 8-aminoquinones, can reduce the number of malaria incidents caused by a Plasmodium species.

Zoonotic malaria is possible but rare. Malaria caused by P. knowlesi that naturally infect non-human primates has been considered a potential threat to human health through zoonosis.

Malaria and Plasmodium Biology

All Plasmodium species share a similar life cycle of two parts:

- Parasite infection of a vertebrate host

- Transmission of malaria from the infected vertebrae hosts to another by an insect factor

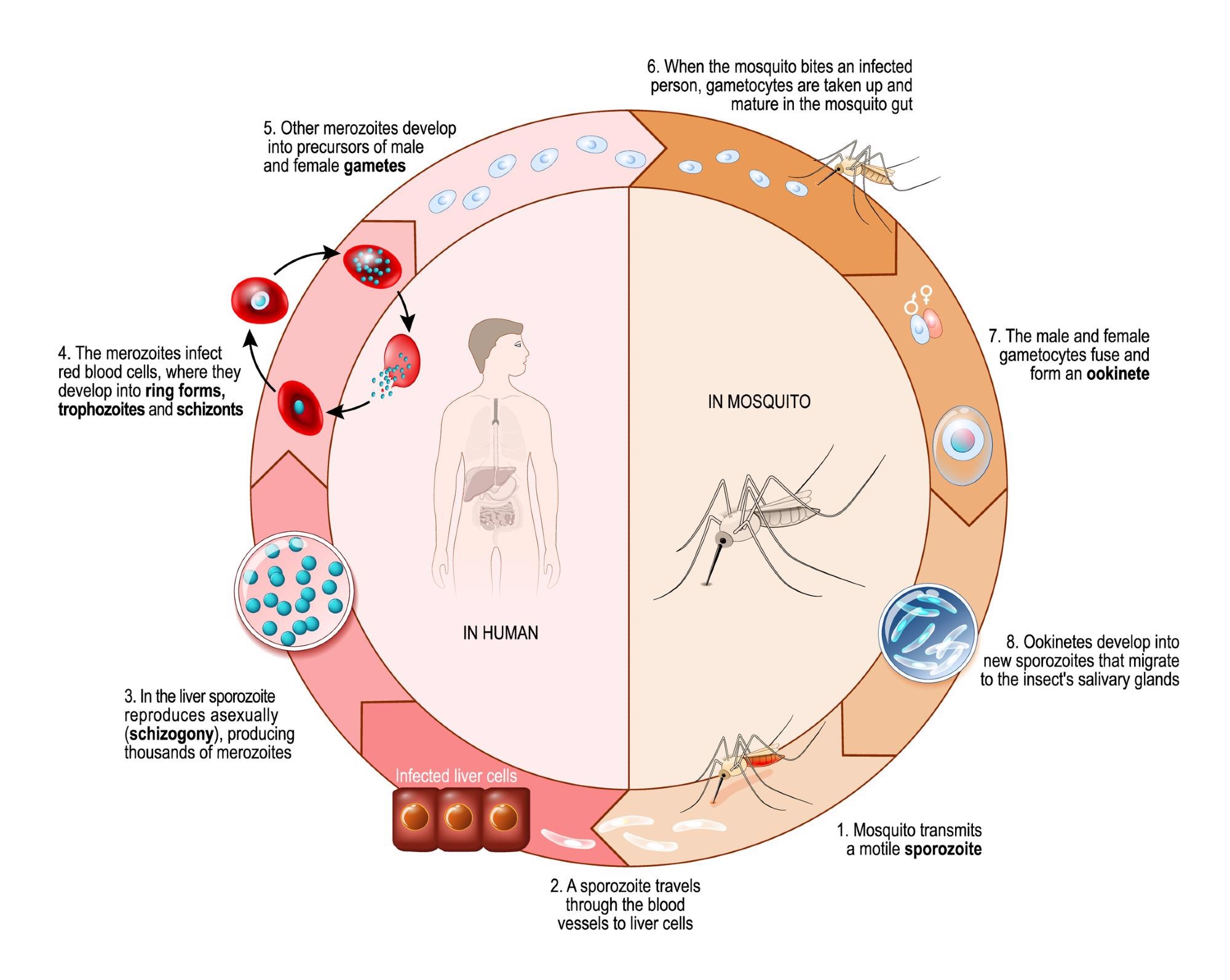

The Plasmodium life cycle begins when sporozoites, produced in the factor, enter the blood of the vertebrate host after being bitten by a mosquito. Sporozoites deposited in the dermis quickly travel to the liver, where they invade hepatocytes. Here they multiply rapidly, increasing by thousands in a process called schizogeny (asexual multiplication).

The malaria infection cycle begins with the injection of sporozoites into the skin by a female anopheline mosquito.

The sporozoites enter the vasculature and are transported to the liver where they exit through the Kupffer cells and enter a hepatocyte. The sporozoites active invasion is preceded by traverse movement in the liver until a suitable hepatocyte is found. When encountered, they form a parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) and undergo schizogony until daughter merozoites are released in compartments of merosomes into the vasculature.

Once the merozoites encounter erythrocytes, they begin a chronic cycle of asexual reproduction in the bloodstream. Some of these asexually reproducing merozoites will undergo gametocytogenesis as a consequence of genetic reprogramming. Oocyte stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease.

Within 15 days, gametocytes are isolated and continue to develop in the bone marrow. Once they have matured, they enter the peripheral circulation. Here, they are ingested by a mosquito and travel to the mid-gut where they form extracellular male and female gametes. Reproduction occurs as a result of the fusion of the male microgamete and female macrogamete to form a zygote. Over 24 hours, this transforms into an ookinete that migrates through the mosquito midgut epithelium where it becomes an oocyst (hardy, thick-walled stage of the parasite lifecycle in which the ookinetes are motile and elongated). The oocysts grow and burst to release sporozoites; these migrate to the mosquito’s salivary gland. When sporozoites are inoculated into a new human host, the malaria life cycle continues.

The life cycle of a malaria parasite. Image Credit: Designua/Shutterstock.com

Clinical Features of Disease and Pathogenesis

Malaria infection in a naive individual almost always produces a febrile (showing the symptoms of a fever) illness. The symptoms that accompany malaria are not specific and include headache, nausea, muscle pain, and rigors. Symptoms will go into remission after a few days if the patient is treated with appropriate drugs.

In the case of the falciparum species, treatment will eradicate the infection, with any return of infection symptoms reflecting an incomplete treatment combat resistance to drugs, or a new infection. In the case of P. vivax and P. ovale, relapses can occur from dormant liver resident hypnozoites.

Untreated or partially treated malaria infections often follow the same trajectory. After a period of symptoms with varying severity, the illness gradually wears off and the parasite becomes desensitized and can be controlled at a low level. Symptoms can occur in intervals over the following weeks and months and are associated with an increase in parasitemia. Waves of parasitemia tend to be lower and symptoms are less pronounced until eventually the infection is resolved.

Malaria continues to pose as one of the global leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Plasmodium falciparum employs numerous immune evasion mechanisms and an efficacious vaccine has remained elusive. Recently, however, the World Health Organization has recommended the use of the RTS, S/AS01 (RTS, S) malaria vaccine in children in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions.

Key findings from pilot studies have demonstrated that the vaccine is feasible to deliver combat and shows a strong safety profile. It has the ability to reach previously isolated communities and plans for a broader rollout, with the adoption of the vaccine as part of national malaria control strategies based on individual countries, are underway.

References:

- Venugopal K, Hentzschel F, Valkiūnas G, et al. (2020) Plasmodium asexual growth and sexual development in the hematopoietic niche of the host. Nat Rev Microbiol. Mar;18(3):177-189. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0306-2.

- Meibalan E, Marti M. (2017) Biology of Malaria Transmission. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a025452.

- Cowman AF, Healer J, Marapana D, et al (2016) Malaria: Biology and Disease. Cell. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.055.

- Milner DA Jr. (2018) Malaria Pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a025569.

Further Reading