Britain has been home to many pioneers of immunology, ranging from cellular biologists to virologists and biochemists. This article aims to provide a brief overview of Britain's history in this vital field.

Juan Gaertner | Shutterstock

Juan Gaertner | Shutterstock

Developing the world's first vaccines

One of the hallmarks of modern preventive medicine is immunization. Known as the father of vaccination, Edward Jenner he performed an ethically doubtful experiment (by today’s standards) but succeeded in proving the effectiveness of vaccinating against smallpox by innoculating a child with cowpox.

A key adjuvant in vaccines is alum (potassium aluminum sulfate), which boosts its efficacy enormously, though the mechanism is unknown. The reason may be that they produce the same effect on the immune system as certain bacterial or viral antigens, thus mimicking natural infection and producing an enhanced immune response.

This substance has been used in vaccines since 1926, when Alexander Glenny, at the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories, London, reported on its benefits in diphtheria immunization. This has led to its widespread use in vaccines. Other salts of aluminum, like its phosphate or hydroxide, or mixed salts, are also effective.

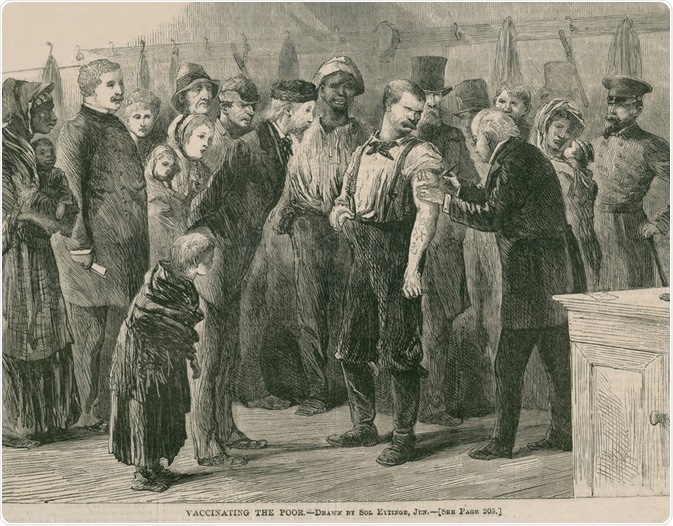

Vaccinating the poor of New York City against smallpox in 1872. In 1863, mass production of smallpox vaccine was developed, allowing for broad immunization of North American and European populations.(Everett Historical | Shutterstock)

Epidemiology meets immunology

In 1854, John Snow identified cholera as a water-borne disease rather than a miasma, or airborne plague. He traced the cases by location in one major outbreak in London, and found that the houses affected were placed around the well of Broad Street where water was hand-pumped. He came to the conclusion that the well contained the source of infection.

With commendable zeal, Snow got the civic authorities to remove the handle of the hand pump – a simple and completely effective measure to contain the epidemic. He was among the first successful epidemiologists, proving the source of infection to be a cesspool containing human waste, which had leaked into the well spring.

Proving the role of the immune system in allergic responses

Ten years later, in 1865, Charles Blackley of Lancashire tested the theory that grass pollen can cause skin allergy. This physician, who originally tested the theory on himself, was the founder of the skin prick test, which has proved immensely useful in detecting specific allergy to drugs, dust and pet dander, amomgst other s.

For over 10 million people in England, summer months are far from pleasant because of hay fever. This common allergic condition is caused by the entry of pollen into the airways, especially from grass.

While the link between hay fever and pollen had been established since the beginning of the last century, it was in 1911 that Leonard Noon of St Mary’s hospital reported his revolutionary desensitization experiments.

Leonard injected grass pollen under the skin to induce immunity to the allergenic substance. John Freeman, his colleague and successor, thus initiated the early form of immunotherapy. This was later carried forward in a clinical trial by William Frankland, also of St Mary’s, in 1954, which set the practice of immunotherapy for allergens on a firm footing.

Anaphylaxis is a major health risk with allergy. In the 1950s onwards, John Humphrey was a pioneer in studies on immune cells, reporting on how anaphylaxis works, as well as the way memory cells are generated.

Memory cells are immune cells that enable rapid immune response to a previously encountered antigen. Radiolabeled and fluorescent-labeled antigen determination was part of his work, and he set forth the role of the antigen in immune tolerance and antibody production.

Transplants and more

Skin grafting was actively explored by Peter Medawar, the father of transplantation, often regarded as the greatest biologist of that time. He became interested in grafting because of the need for treating severely injured soldiers and airmen who had sustained serious burns in World War II.

Medawar wanted to understand why it was not possible to take skin from a donor and graft it to another person (allograft or homograft), while it was quite feasible to graft skin from one area to another (autograft). This, he hypothesized, was because of tissue rejection, since the grafted tissue taken from another individual lacked the self-antigens.

This concept had been put forward by the Australian immunologist Frank Burnet. He hypothesized that the introduction of a foreign substance into an immunologically immature embryo would lead to its being accepted as self. Thus, even if the substance was again introduced to the individual, no specific antibodies would be generated against it. This was later named immunological tolerance.

While Burnet explained the theory behind immunological tolerance, it was Medawar who proved the process experimentally at University College, London. For this seminal work, both scientists received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1960.

nobeastsofierce | Shutterstock

nobeastsofierce | Shutterstock

Cellular and humoral immunity is discovered

In 1961, another important discovery was made. Jacques Miller, studying leukemia at the Chester Beatty Laboratories in London, switched to the thymus. He found something astonishing: removal of the thymus produced immunodeficiency. Later studies confirmed this, showing that the thymus produced one class of white blood cells called T-lymphocytes.

Between 1960 and 1980, Delphine Parrott worked on T-cell function as well, advancing organ transplantation and clarifying thymus function in health and disease.

Robert Coombs was the founder of clinical immunology, putting forward a range of important diagnostic tests and textbooks which changed how people understood the functioning of antibodies. The Coombs test (1967) detects antibodies against the RhD antigen on red cells which is responsible for hemolytic reactions against mismatched blood cells in fetal life and during transfusions.

From 1968 to 1981 Deborah Doniach pioneered the study of autoimmune disease of the thyroid, liver, adrenal and other endocrine glands.

Another step in understanding immune function was taken when the Y-shaped antibody structure was discovered by Rodney Porter of Oxford and the US scientist Gerald Edelman, using two different methods.

The vast specificity of antibody molecules is due to this structure, which has a basic common structure but millions of possible variations produced by different amino acid sequences in the arms of the Y. They received the 1972 Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery.

Brigitta Askonas was known as the Mother of immunology during this period when she headed the division of immunology at the National Institute for Medical Research. She found that B cells produced antibodies as part of the immune response, and enlarged current understanding about how humoral and cellular immunity works.

Hybridomas and the modern era of immunology

The MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge saw another fundamental discovery with the invention by Cesar Milstein and Georges Kohler of hybridoma technology. This fuses antibody-producing B cells with myeloma cells to allow the production of unlimited quantities of identical antibodies directed against specific antigens.

These are called monoclonal antibodies and have transformed scientific research, diagnostic techniques and the immunotherapy of some forms of cancer. Milstein and Kohler shared the 1984 Nobel Prize for this work with Niels Jerne.

Alister Voller and Dennis Bidwell of the Institute of Zoology in London reported on the use of the microplate for rapid testing in both field and laboratory, of multiple blood samples for microbes dangerous to humans, using the ELISA technique. They left the technology open for unlimited use, used globally to improve the health of literally millions.

The contribution of British immunologists to the health and wealth of the world is thus quite striking in many invaluable areas of knowledge, and the setting up of premier institutions of science during the last century will help to advance this field still further.

Further Reading