What is the Microbiome?

There are more than ten times as many bacteria and other microorganisms in our bodies as there are human cells. Bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microorganisms reside within the digestive tract, primarily within the intestines, and play a fundamental role in digestive and immune health.

The microorganisms are primarily ‘good bacteria’ and maintain a symbiotic relationship with the host. A balanced diet and active lifestyle can promote and maintain the number of ‘good bacteria’ in the gut. However, these colonies may become compromised by ‘bad bacteria’ leading to an imbalance in the gut flora (“dysbiosis”) that can lead to many health problems ranging from inflammation to colorectal cancer.

‘Bad bacteria’ can be promoted by many activities such as overuse or misuse of antibiotics, lack of sleep, elevated stress levels, excessive alcohol consumption and a lack of ‘prebiotics’ such as fibrous foods, nuts and lentils, as well as failure to have a diverse, fresh and balanced diet.

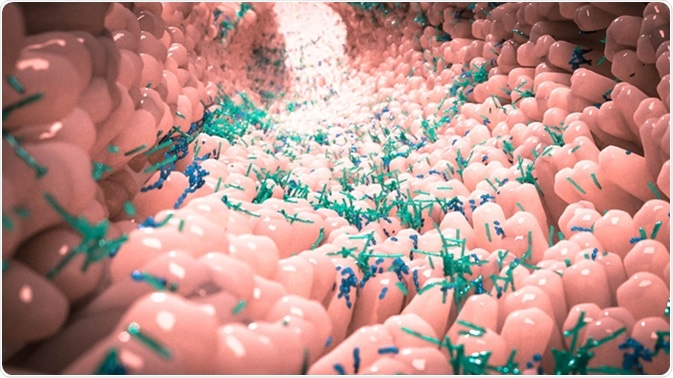

Microbiome in human gut. Image Credit: Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics / Shutterstock

The Microbiome and Alzheimer’s Disease

The gut contains around 500 million neurons which comprise the enteric nervous system (ENS). The interaction of the gut with and influence upon the nervous system, and vice versa, is known as the ‘gut-brain-axis’. Much recent evidence suggests that the gut-brain-axis may be implicated in a range of neurological disorders including multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease and dementia.

A recent study showed that there were alterations in the composition of gut bacteria in patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared to healthy controls. For example, Clostridium and Bifidobacterium species were less abundant in patients with Alzheimer’s, whereas Bacterioides and Gemella were more abundant, to name a couple of examples.

Furthermore, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) markers for Alzheimer’s pathology, such as the levels of amyloid-beta protein, could be correlated with a change in the number of certain bacteria in the gut. For example, a decrease in the number of Bifidobacterium (which is known to be reduced in Alzheimer’s) could directly be correlated with high levels of amyloid-beta-42 (Aβ42) in the CSF of patients with Alzheimer’s. The greater the discrepancy in the levels of gut bacteria, the greater the level of pathological markers in the CSF.

The Gut Microbiome and Alzheimer's Disease

What effect do different bacteria have on the gut and the brain? Understanding this question is a difficult task and it took studies of individual bacterial families to elucidate potential mechanisms. For example, obese mice on a high-fat diet often exhibit some cognitive deficits, but show an improvement in symptoms and weight-related inflammation when supplemented with the bacterium L. helveticus R0052.

Conversely, some microorganisms can induce and facilitate inflammation through the gut-brain-axis. Bacteria that secrete lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and amyloid can trigger profound inflammatory changes within the gut, and therefore within the brain. Inflammation within the gut can cause the gut to become ‘leaky’ as well as causing the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) to become more permeable. As such, inflammatory molecules can enter the brain through a compromised BBB to trigger brain inflammation, which could trigger or exacerbate Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. One such bacterium that may induce neuroinflammation and thus initiate neurodegeneration through the gut is Bacteroides fragilis.

Preventing and Treating Alzheimer’s

An accumulation of recent evidence suggests that an imbalanced gut microbiome (dysbiosis) could lead to Alzheimer’s disease and wider neuroinflammation through the gut-brain-axis. Promoting ‘good bacteria’ relative to ‘bad bacteria’ in the gut may be important in maintaining good digestive, immune and neurological health.

Fresh plant-based foods, probiotics in yoghurt, as well as prebiotics in the diet, naturally promote a good balance of microbiota in the gut. These include, but are not limited to, fruits, vegetables, onions, garlic, nuts, lentils, high fiber foods and polyphenols (as in green/black tea). These foods can promote a reduction in the population of Bacteroides, and instead encourage bacteria like Prevotella. Maintaining good gut health should prevent gut-mediated neuroinflammation. A Mediterranean diet is rich in such foods and has been shown to reduce the risk of not only heart disease, diabetes and cancer, but also dementia.

Our understanding of how certain gut bacteria can influence brain health is a developing field. For example, research has shown that the administration of Bifidobacterium to certain mice may improve cognition. However, much more work is needed before any research relating to the gut microbiome translates into effective therapies for Alzheimer’s disease.

The evidence thus far has proven a strong connection between gut microbiota and brain health (especially with respect to Alzheimer’s) and this may serve as a crucial therapeutic research avenue in the future.

Further Reading